Preserving Wisdom, Confronting Algorithms |

|

Indigenous Knowledge (IK) is increasingly recognized in global policy dialogues as a vital component of sustainable development. It is highlighted in international agreements such as the Convention on Biological Diversity, the Paris Agreement, and the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. These documents stress the importance of Indigenous peoples' worldviews, languages, and practices - especially in confronting challenges like biodiversity loss and climate change. Yet as we enter the age of Artificial Intelligence (AI), new questions emerge. What is the role of Indigenous Knowledge in an increasingly algorithm-driven world? Can it co-exist with the logic of AI, or is it at risk of being ignored - or worse, co-opted?

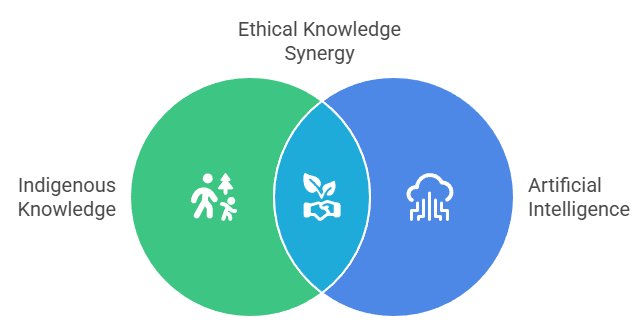

Bridging Indigenous Wisdom and Artificial Intelligence This Concept Note explores how Indigenous Knowledge fits within the emerging AI landscape, the tensions between the two, and opportunities for a more inclusive, ethical, and pluralistic approach to knowledge management. 1. The Nature of Indigenous Knowledge

Indigenous Knowledge is grounded in lived experience, oral transmission, and deep, place-based observation. It is holistic and relational?often integrating ecological, cultural, and spiritual dimensions in ways that are fundamentally different from the compartmentalized, data-driven approaches of Western science and technology. Whereas AI tends to emphasize abstraction, prediction, and automation, Indigenous knowledge systems prioritize continuity, balance, and responsibility within ecosystems. These contrasting foundations create both challenges and possibilities. 2. Tensions Between AI and IK The intersection of AI and Indigenous Knowledge is not neutral. It is shaped by histories of colonization, power asymmetries, and assumptions embedded in technological design. These tensions reveal the risks of marginalization and misrepresentation, and call attention to the need for caution and critical reflection. The following sub-sections outline three core areas where these tensions manifest most sharply. a. Epistemic Injustice and Exclusion AI systems are built on data?mostly from Western, industrialized contexts. Indigenous languages, customs, and ontologies are often absent from training datasets, leading to systemic exclusions. When Indigenous data is included, it is frequently done without consent or proper representation, contributing to a form of digital colonization. b. Risk of Misappropriation AI may glearn fromh Indigenous Knowledge, for example, in areas like agriculture, medicine, or climate resilience, without acknowledging or compensating the communities who generated that knowledge. This replicates long-standing patterns of extractive research and knowledge theft. c. Incompatibility of Worldviews Many AI systems are built upon assumptions of objectivity, efficiency, and universality. Indigenous epistemologies, on the other hand, are local, contextual, and value-laden. Trying to encode IK into AI models risks flattening or distorting it into something it is not. 3. Opportunities for Ethical Alignment Despite the risks, there are emerging efforts that demonstrate how AI can be harnessed in respectful and empowering ways to support Indigenous Knowledge systems. These examples point toward pathways for ethical alignment?where AI does not dominate or distort, but instead collaborates with Indigenous communities to serve shared goals. The sub-sections below highlight three such opportunities. a. AI for Cultural Revitalization Projects are using AI to preserve and promote Indigenous languages through speech recognition, translation tools, and digital archives. Others are creating virtual museums, interactive maps, or oral history repositories that protect cultural heritage while increasing public awareness. b. Data Sovereignty and Indigenous AI Movements like Indigenous Data Sovereignty and Indigenous AI position Indigenous peoples not just as data subjects, but as data stewards and technology creators. These initiatives advocate for control over how data is collected, stored, shared, and used?and call for AI systems designed in ways that align with Indigenous values. c. AI and Local Environmental Knowledge When guided ethically, AI can amplify IK in domains such as wildfire prediction, water management, or biodiversity monitoring. The key is meaningful collaboration, not extraction?technology as a tool in Indigenous hands, not as a top-down imposition. 4. Towards Knowledge Pluralism in AI Governance The rise of AI demands a rethinking of what counts as knowledge and who gets to define it. Indigenous Knowledge must be seen not as a supplement to grealh data or science, but as a valid and necessary system of understanding. Global governance frameworks for AI?such as those being developed by UNESCO, the OECD, and the EU?should explicitly include Indigenous perspectives and rights. Ethical AI is not only about fairness, transparency, and privacy. It must also be about epistemic inclusion and the protection of diverse knowledge systems. 5. Respect, Reciprocity, and Rebalancing In the age of AI, Indigenous Knowledge stands at a crossroads. It is vulnerable to erasure by dominant digital paradigms, but it also offers powerful alternatives to how we think about intelligence, sustainability, and the future of humanity. Respecting Indigenous Knowledge in the AI era means shifting from extractive to reciprocal models. It requires humility in design, shared governance, and a commitment to knowledge justice. If we want AI to serve all of humanity, we must first ensure it respects the oldest knowledge systems we have.

|

Hari Srinivas - hsrinivas@gdrc.org Hari Srinivas - hsrinivas@gdrc.orgReturn to the Knowledge Management Page |